3 Effective Strategies For Overcoming Record Loss In Burned Counties

*This post may have affiliate links, which means I may receive commissions if you choose to purchase through links I provide (at no extra cost to you). All opinions remain my own.

One of the last things anyone wants to discover in their genealogy research is a destroyed courthouse or that where their ancestors lived is a “burned county.”

It can feel very disheartening and like you’ll never get answers or move back another generation on your family tree.

While researching in these areas is more challenging, it is possible to make progress on your family history. You’ll need to get more creative and likely look for records that may be harder to access with less direct information.

It also requires more patience, like researching brick wall ancestors. You must be open to looking in places you’ve never used before, like certain archives, and to go page by page through unindexed records. To get around burned county challenges, you have to use any type of record you can get your hands on to replace the lost information.

In this article, I’ll go over what “burned counties” are and share tips for researching regions that have experienced record loss.

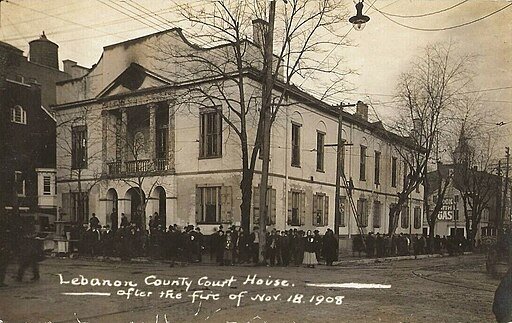

Image: The Lebanon County Courthouse after the fire of November 18, 1908, via Wikimedia Commons

What are burned counties?

Despite its name, a burned county is a catchall term in genealogy for any place that has faced a loss of records. While fires are a common reason, reasons could also be floods, mold, war, or government officials purposely destroying records because they didn’t see the value in them.

Some famous examples include the 1890 census, the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and fire, the 1922 Four Courts Fire in Ireland, and the Civil War.

Related posts:

11 Smart Strategies For Searching For Ancestors Who Changed Their Name

How and Why to Research Your Collateral Ancestors

How To Avoid A Brick Wall And Research Your Ancestors With Common Names

How To Effortlessly Analyze Old Obituaries And Verify Their Clues

Why you shouldn’t lose hope researching in a county with record loss

Finding out that the area your ancestors lived in experienced a disaster and lost records can feel devastating. I know from personal experience. My mom’s family is from Okinawa, which was significantly affected by World War II, with many documents lost.

But even if you’ve heard that your family is from a “burned county,” don’t take everything at face value and lose hope.

Everything wasn’t kept in courthouses and even if what you’re looking for was, it’s possible that not everything was wiped out. (I’ll go into this more below.)

If you focus too much on the lost records, rather than what may survive, you can get tunnel vision blinding you to other records that can have the answers you seek, albeit not in the exact way you were expecting.

Related posts:

Why Isn’t My Ancestor in the Census?

How To Use Online Family Trees The Right Way

How Probate Records Can Help You Find Your Female Ancestors

How To Trace Women In Your Family Tree With Veterans’ Pension Records

3 tips for researching in a burned county

1) Get to know the area

First, research when the disaster occurred. It’s possible it happened before your ancestor was born or lived there, so the records you need do exist.

Then research the county to uncover what records are still available and what is truly lost. You may find that only certain types of records or certain years are gone. Using a locality guide template will help you collect this information in one place and guide you through surviving record collections.

Think about what other resources might exist in the area that could benefit your search, like:

Genealogy and historical societies

Local libraries and archives, including colleges, church archives, and museums

County history books with more details about the disaster

Town historians

Newspaper and journal articles about the scope of the disaster or the area in general

As you talk to people at the various repositories, remember that staff or volunteers may not be completely familiar with what does or does not exist, especially for older records. I heard a tip from genealogist Tom Jones to gently push back when told that a record collection no longer exists, especially when you feel confident that some or all the records are available. Of course, always be respectful, but you can ask them to double-check or order a record to see what happens.

2) Look at the bigger picture.

The county courthouse may have burned, but are you sure that records about your ancestors were actually there?

Look at where your ancestors lived on a map and check the distance to the courthouses and clerk’s offices in the surrounding counties. They may have lived in one county but were geographically closer to a courthouse in the neighboring county and went there for legal and civil matters. People often went to whatever location was most convenient for them, despite where they lived.

If your family migrated in or out of the area, it’s possible that the records you want don’t even exist in that burned county and are somewhere else. Use a timeline to track when your family lived in each specific place to determine when they may have created records.

Boundaries may have also changed. If your family lived in a place formed from another county, the records you need may be in the “parent” district, which might not have suffered a loss of records.

3) Seek out alternative records.

Sometimes the documents you need truly are gone due to a flood, fire, or a town clerk who decided they didn't need to save older records.

What can you do in these situations?

While we want to learn as much as possible about our ancestors, sometimes we have to accept that we may not find the exact document or information we hoped for and make do with whatever tidbits we can uncover.

This is where alternative records come into play. These can have similar or identical information to the lost records.

These may not be the original, primary records we typically seek out, but sometimes it’s all we have to work with.

Some potential alternative sources are:

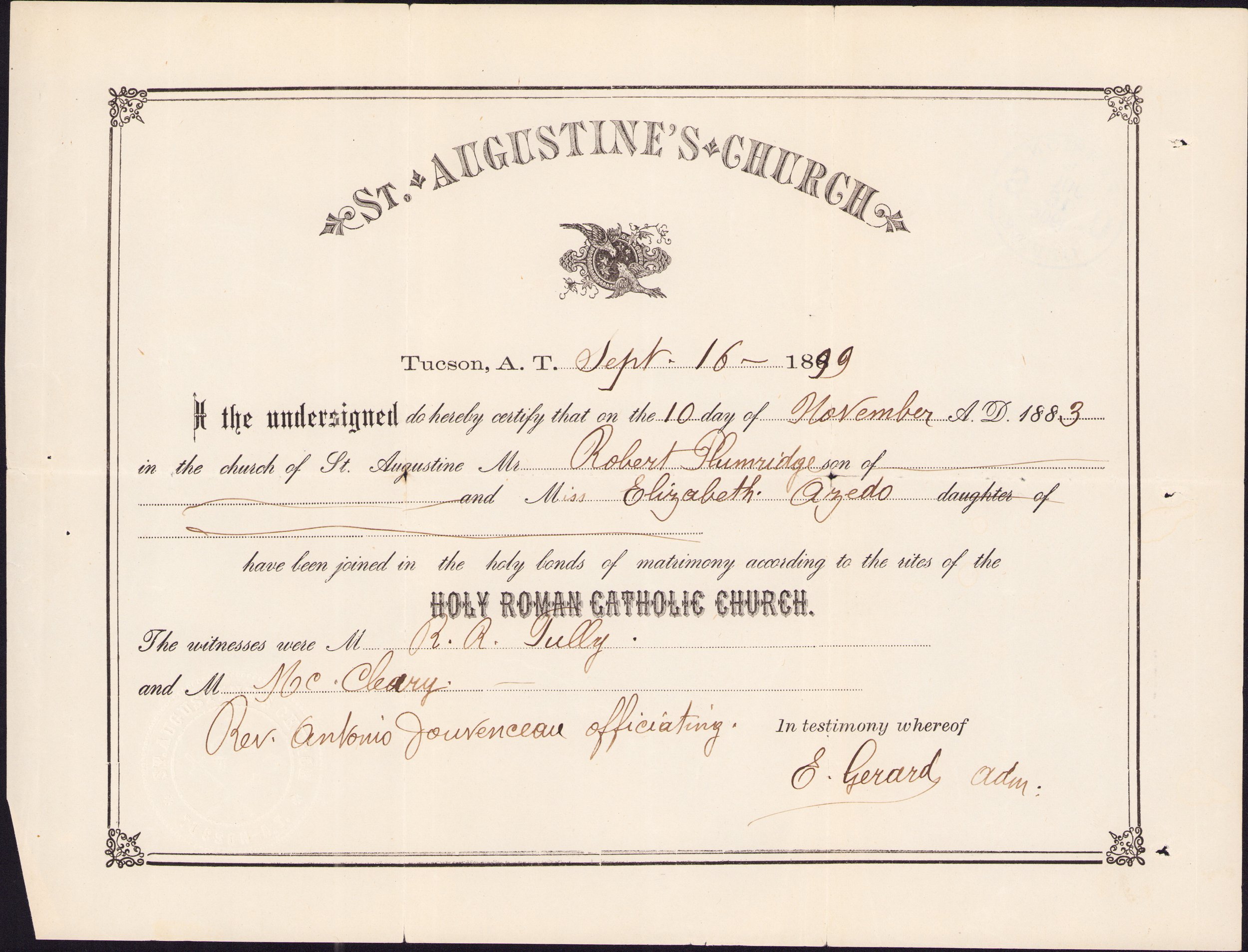

Pension records. I’ve found marriage and baptism certificates in Civil War pension files, as well as children and their birthdates, death information, previous spouses, and affidavits attesting to when someone was born when no record exists.

Marriage certificate of Robert Plumridge and Elizabeth Azedo from Robert’s Civil War pension file

Church records for births, deaths, and marriages

Land records can name family relationships.

Newspapers gossip columns, obituaries, feature articles, and divorce and probate notices

Home sources like family bibles can also give biographical details.

Transcriptions and abstracts. Sometimes, genealogists transcribed or abstracted important documents before a disaster.

The 1890 Veterans census

Tax records. The state received duplicate copies, which may exist.

Vital records. Again, many counties sent duplicate copies to the state.

In some cases, people recreated important legal documents after a record loss, like deeds or wills.

You never know where you’ll find vital information. I’ve found baptism and marriage certificates in orphanage collections!

Marriage certificate in the San Francisco Protestant Orphan Asylum records

Related posts:

Solve Your Genealogy Brick Wall: Review and Analyze Your Research

How To Evaluate Sources For Confidence In Your Genealogy Research

Solve Your Genealogy Brick Wall: 10 Ways To Widen Your Research Net

How To Solve Your Genealogy Brick Wall With Surname Research

Final thoughts

In the course of our research, we sometimes stumble upon the disheartening reality of burned counties, whether from fires, hurricanes, or other reasons. But there is still always hope. With perseverance and an open mind, we can piece together resources to reconstruct our ancestors’ stories and fill in what was lost.