How To Evaluate Sources For Confidence In Your Genealogy Research

*This post may have affiliate links, which means I may receive commissions if you choose to purchase through links I provide (at no extra cost to you). All opinions remain my own.

Stuck on a difficult ancestor?

One of the first steps to take in trying to break through a genealogy brick wall is reviewing what you have.

The next great step to take is to evaluate the information you have. Once you’ve gathered everything you know together and reviewed it, you are ready to weigh pieces of evidence against each other.

You know a lot more about genealogy research now, so you’re in a great position to look at that record and assess information with a fresh perspective.

Maybe you found something when you first started working on your family tree and didn’t think about where the information was coming from. It was exciting to add things to your family tree.

Or you found someone’s tree online and copied it to your own without double-checking it. It happens.

Reappraising everything might be the ticket to making progress on your family tree research.

Let’s discuss how to evaluate sources to knock down your research roadblocks.

Related posts:

6 Common Genealogy Mistakes and How to Avoid them

7 Simple Steps to Creating a Genealogy Timeline and Why You Need One

Why is it important to evaluate sources?

Genealogical analysis is crrtical to making sure you have found the right person, in the right place, at the right time.

As we research our family history and gather facts and stories, it is inevitable that we’ll find some records that contradict each other. Someone not aging correctly from census to census. Someone not aging correctly from census to census. Different maiden names.

It’s also likely we’ll find someone with the same name as our ancestor in the same general area, and/or have to research an ancestor with a common name.

On top of that, recordkeeping and consistency with things like the spelling of names weren’t as important in the past as today.

To feel confident about our research, we must be consistent about evaluating sources of information.

Analyzing sources consists of looking at three components of each: the source, its information, and its evidence.

Related posts:

Why Isn’t My Ancestor in the Census?

How To Use Online Family Trees The Right Way

Evaluating sources in genealogical research

The first step in this strategy is to evaluate the source itself.

Sources are where you find information – like documents, books, and websites – which we can then use as evidence.

There are three types of sources:

1) Original – the first time something was recorded (spoken or written). Examples are baptisms, tax records, passenger lists, military records, and diaries.

These sources are more dependable because the information is in its original form, so mistakes are less likely.

Of course, this can also mean that their condition is fragile, the ink has faded, or pages are unreadable or missing. Sometimes you have no choice but to use another type of source.

2) Derivative – altered versions of an original source, like an extract or an index.

These are less dependable because mistakes could have happened when creating them.

In some cases, a derivative source might be all that exists or the only thing you can access.

3) Authored narrative – these take other sources and create a new source, such as a family history book.

Use authored narratives to help point you toward original sources when you can.

Related posts:

How To Avoid A Brick Wall And Research Your Ancestors With Common Names

Solve Your Genealogy Brick Wall: 10 Ways To Widen Your Research Net

How to evaluate information in genealogy research

The next piece of evaluating sources is analyzing information found within them. Information is the facts you find in a source.

Like sources, there are three types:

1) Primary – based on firsthand knowledge of an event, from witnessing or participating in it.

2) Secondary – this type of information comes from someone who didn’t witness an event and is hearsay.

3) Undetermined – this is when you don’t know who gave the information so you can’t judge how accurate the information is.

Censuses are a prime example of this. Anyone in the house or even a neighbor could give information to the census enumerator.

A county history book without citations is another. I have a county history book with genealogical information about my family, but no citations on where that info came from. I want to believe it, but it’s hard to trust.

Just because pieces of information are secondary or undetermined, it doesn’t mean they are not correct or true. But it does mean you should keep searching for primary accounts to back them up whenever possible.

Related posts:

How and Why to Research Your Collateral Ancestors

10 Clues In Historical Land Records For Your Genealogy Research

How to analyze evidence in genealogy research

Analyzing evidence is the final step in evaluating your sources.

Analysis of evidence is how we weigh the information in sources and whether it answers our research question.

1) Direct evidence – this type directly answers our research question.

If you’re researching when someone was born, for example, a birth certificate or a church record would give direct evidence of the birth date.

2) Indirect evidence – information that doesn’t directly answer the question but gives some clues.

If someone started getting taxed when they turned 21 and you find a tax record with them on it, that's indirect evidence that they were legally an adult.

3) Negative evidence – this one is a bit trickier. Elizabeth Shown Mills defines this as “an inference we can draw from the absence of a situation that should exist under particular circumstances.”

One example she gives to explain this is a baptism register that shows several children with “legitimate” in the baptism acts, but the baptism for another child doesn’t say it. The missing “legitimate” from that child’s baptism is negative evidence. This doesn’t mean the baby was legitimate or illegitimate, but that the question needs more evidence to prove or disprove it.

Related posts:

How To Solve Your Genealogy Brick Wall With Surname Research

6 Google Search Tips For Genealogy That Will Save You Hours Of Time

Variations of information and evidence within a source

Each source can have a combination of types of information and/or evidence.

A death certificate has primary information for the date and place of death. But it has secondary information for a date and place of birth unless the informant was a witness to the birth.

Depending on your research question, a source may also have direct and indirect evidence.

As you can see, there are a lot of moving parts to evaluating a genealogical source.

But don’t feel discouraged. It can take time and practice to learn how to assess a source, but soon you’ll be automatically evaluating a source, its information, and its evidence.

Related posts:

11 Smart Strategies for Searching for Ancestors Who Changed Their Name

Developing criteria to assess sources

One of the reasons evaluating sources for credibility is essential is to prevent research roadblocks and ensure the accuracy of your work.

In my post about reviewing what you have another brick wall strategy, I said it was a great time to check the citations for all your sources. Having citations helps you understand the source and judge the reliability of its information and evidence.

As you research, you’ll want to establish some criteria for evaluating sources to follow.

As you examine (or reexamine) your sources, a few questions to ask yourself are:

How trustworthy is the derivative or authored narrative source? Are there references to show where the information came from?

Are there obvious errors or “facts” that don’t make sense based on what you know from other, reliable sources?

Who was the informant? Were they in a position to know about the information you’re looking at?

If so, was the informant reliable about information in other records? One of my 3x great-grandmother's brothers was the only sibling who consistently gave correct information about the family. I trust what I find from his documents more than any other sibling, including her, even if the information is secondary. That said, I still try to find documentation backing up the information he provided.

Related posts:

Why You Need a Genealogy Research Log

How to Strengthen Your Cemetery Research Skills to Find Clues

Evaluating sources examples

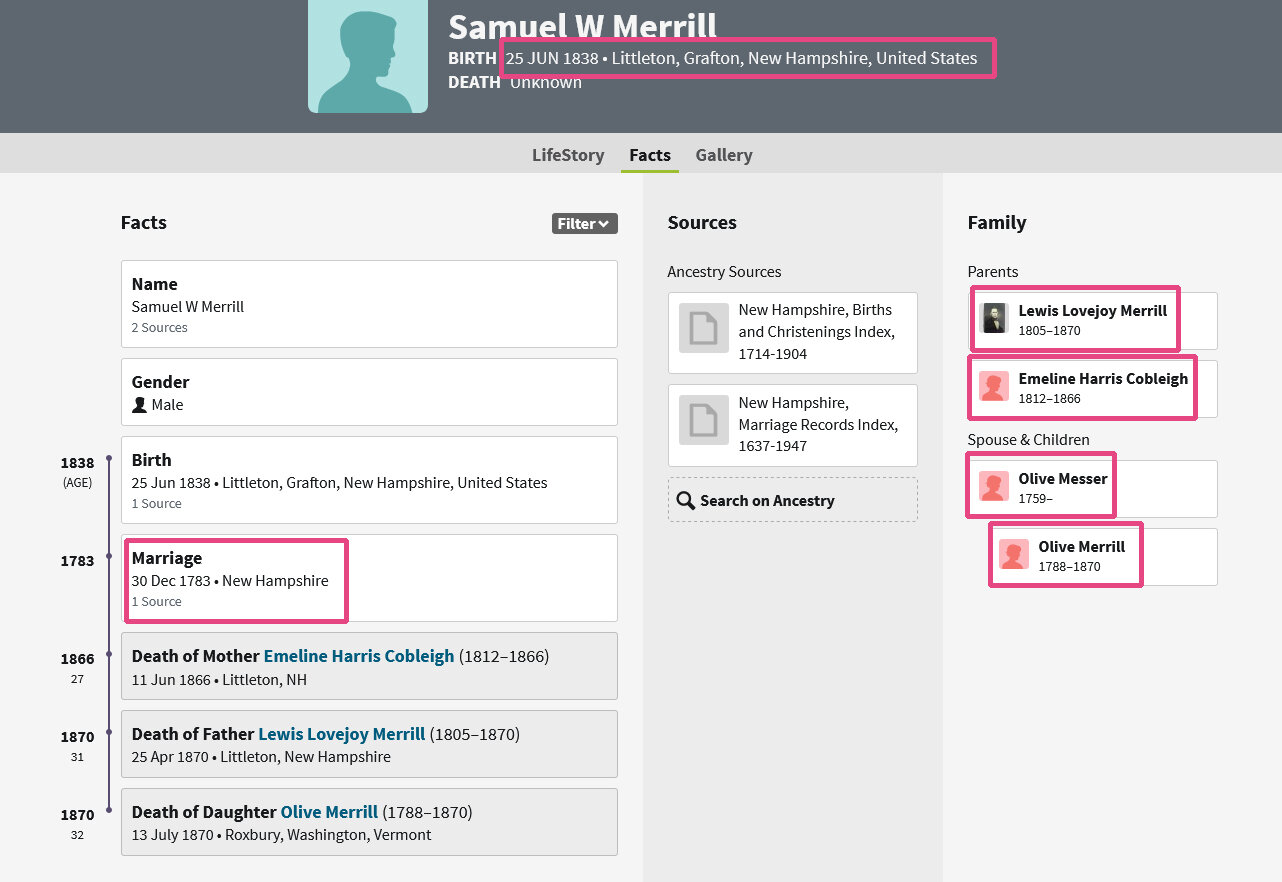

Let’s take an Ancestry tree for the cousin of my 4x great-grandmother as an example of how to apply evidence analysis. This one is a bit of an obvious example to use, but it’s an easy one to show the process.

I’ve been trying to find Samuel Merrill’s parents and children.

You might be able to see the errors right away, but not everyone has. Several people have saved this couple as Samuel’s parents.

The source, an Ancestry family tree, is an authored narrative. It brings together different sources and presents the creator’s findings.

The pieces of information in this source are:

Samuel W Merrill was born on 25 June 1838 in Littleton, Grafton, New Hampshire

Samuel’s parents were Lewis Lovejoy Merrill and Emeline Harris Cobleigh

Lewis Lovejoy Merrill was born in 1805 and died in 1870

Emeline Cobleigh was born in 1812 and died in 1866

Samuel married Olive Messer on 30 December 1783 in New Hampshire

Olive Messer was born in 1759

Their daughter Olive was born in 1788

Are you seeing the issues already? We don’t even need to dig that deep to see that this tree is an unreliable source of information on the parents of Samuel and his birth information.

This tree has Samuel being born 55 years after his marriage to a woman 79 years older than him. His parents were born 46 years and 53 years, respectively, after his wife.

There’s no point in looking at the source citation on the tree for that birth and the parents because it’s clearly the wrong couple.

But what about the marriage to Olive Messer? Could that be correct?

This tree does give a citation for that – the New Hampshire Marriage Records Index, 1637-1947. This index shows a Samuel Merrill married an Olive Messer on 30 December 1783 in New Hampshire and gives a Family History Library film number.

This index is a derivative source. It’s an index based on New Hampshire marriage records. The information is primary, based on firsthand knowledge of the marriage. The evidence is direct evidence of the date of the marriage and state it took place in.

This shows how important it is to find an original source when you can. This index is a great start but doesn’t give the exact location of the marriage or the parents’ names. The parents' names and other details may or may not be in the original, but you don’t know unless you check.

There could be more information about the marriage on the FHL microfilm, which presumably has an image of the source. The next step would be to view that.

Final Thoughts

Like reviewing and re-examining what you already know, appraising what you have is a great brick wall-busting strategy.

It does take patience and practice to think through sources, evidence, and information.

Sometimes everything is very obvious and sometimes you have to think through it a little more.

As you tackle your brick wall (and really, all your research), assess each source you have, every detail in those sources, and the type of evidence those facts are.

When you explore each element of a source, you might realize you were using an untrustworthy source and need more conclusive evidence.

What may have seemed like a great source several months or years ago may not seem like it anymore now that your skills have grown. And if you don’t have citations for information in your tree, using this process will help you find quality sources.

When you can find something closest to an original record with primary information and direct evidence, you’re on your way to solving that puzzle!