10 Terrific Resources For Identifying Your Immigrant Ancestor’s Hometown

*This post may have affiliate links, which means I may receive commissions if you choose to purchase through links I provide (at no extra cost to you). All opinions remain my own.

One of the main things on everyone’s genealogy bucket list is to find their immigrant ancestor’s hometown.

This can be a real challenge when immigrants often noted only their country of origin, but nothing more specific.

I’ve talked to people who want to go right to researching in the country their family came from, thinking that’ll lead them to their ancestor’s birthplace.

But before you start researching in another country, it’s important to learn a person’s hometown (or at least a county or region).

Related posts:

Where To Find Records For Emigrants To The United States

Why Isn’t My Ancestor in the Census?

What is a nom dit and why did my French-Canadian ancestor have one?

14 Books That Will Help Your Irish Genealogy Research

Why you need to identify the hometown before researching overseas

There are a couple of reasons it’s important to first figure out where someone was born before trying to do genealogy research in another country.

First, records in other countries are often organized by locality, whether it’s a parish, town, or county. Yes, the same is true of the US. But files may be stored in archives across the country. While the country may have one central digital archive, the documents aren’t always indexed so you’d have to browse through the images. You can’t start unless you know where to look.

Even if there are indexes, it’ll be harder to learn which person is your ancestor if you come across people with the same or similar names from all over the country.

At the very least, you need to narrow down the area to search to a region like a county.

Locating your ancestral hometown will also help you see what resources are available for the place and time you are researching.

Preparing to research your ancestor’s birthplace

Before you start diving into your research, take some time to review what you know.

This can lead you to the collections are going to be the best to look into first. Reviewing key facts about your ancestor will also make it easier to see potential matches in your research.

Some questions to ask yourself are:

Do you know if their name changed? If so, what other names did they use? Write down all the spelling variations.

What was their religion?

About when did they immigrate, and which ports were most likely for them to arrive at?

Who were their spouse and children and when and where were they born?

Did other family members also immigrate, and where did they live?

Did your ancestor serve in the military?

Were they married in the “old country” or in the US?

Did they become a citizen?

It’s also helpful to know about when they arrived. If you don’t already know their immigration year, use a US census immigration worksheet to narrow down their approximate arrival year. Depending on where in the world they came from, there may also be clues on the census to point you towards a research starting place (i.e. place of birth was Bavaria).

Once you put together the basics about their life, you can look for the US resources that are most likely to have birthplace information.

You may need to use a variety of the sources discussed below to identify where your ancestor was born.

Related posts:

How and Why to Research Your Collateral Ancestors

10 Books to Boost Your Scottish Genealogy Research

How to Find Italian Vital Records on FamilySearch

Why You Need to Use Libraries and Archives in Your Genealogy

1. Home sources

Home sources are the items your family already have. These include things like letters, telegrams, diaries, and family bibles.

These great resources can have direct and indirect clues on where your family came from.

2. Censuses

Censuses are the next essential type of record that you can use to discover a hometown. While they usually won’t tell you exactly where someone was born (besides a country), they do narrow down when your relative arrived and when they became a citizen.

This can lead you to other sources like naturalizations, passenger lists, and military records, which I’ll discuss later.

While all censuses from 1870 and on ask for the country of birth, there are more immigration clues you can find in these.

The censuses with immigration information are:

1870 census has a column for "Male Citizens of the U.S. of 21 years of age and upwards." This can mean they had been naturalized.

1900, 1910, 1920, and 1930 all ask the year the person immigrated to the US.

1900, 1910, 1920, 1930, 1940, and 1950 censuses ask for naturalization status.

The 1920 census also gives the naturalization year.

1910, 1930, 1940, and 1950 ask for military service.

The 1910 through 1940 censuses also ask for the person’s native language.

My US census immigration worksheet can help you quickly put together and analyze the immigration data you get from the censuses.

3. Church records

Church records are a very important resource not only for births, marriages, and deaths but also for discovering places of origin.

Because church records often began before vital records, you have a good chance of coming across something for your family.

Look for baptisms and christenings, marriages, and burials for your relatives and their children.

But don’t stop there! Look for church histories, meeting minutes, and newsletters. There could be hints about where a church member came from and family relationships.

Research all the witnesses for the events that you dig up to uncover where they were from. Those witnesses are likely relatives. Chain migration was common, so look for patterns of people coming from the same area and/or with the same surnames.

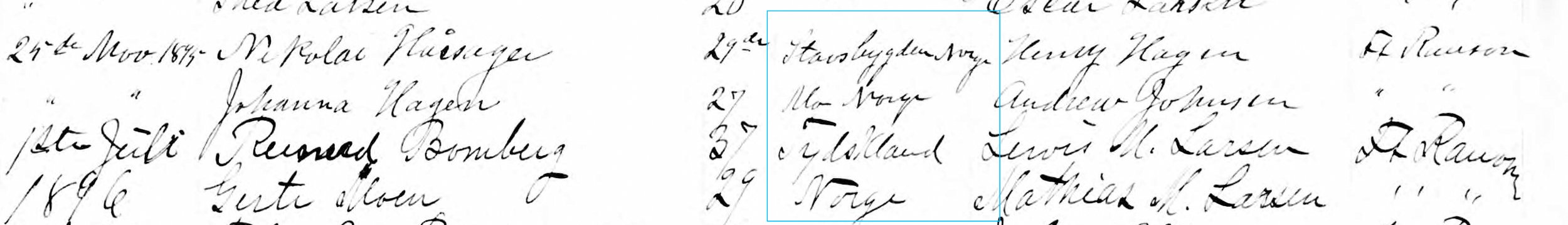

4. Passenger lists and border crossing records

Passenger lists are more useful if your family arrived after 1906, when ship manifests stated the immigrant’s place of birth. You can also learn of the person’s closest relative in their home country and their address.

Before 1906, you can learn details like if they were joining a relative and their last residence, but exact hometowns were rare. Their last residence may not have been where they were born, although it’s still a clue.

Look for both arrival and departure lists. They might have traveled back to visit family.

Mexican and Canadian border crossings begin about 1895 for Canada and 1903 for Mexico and name where the person was born.

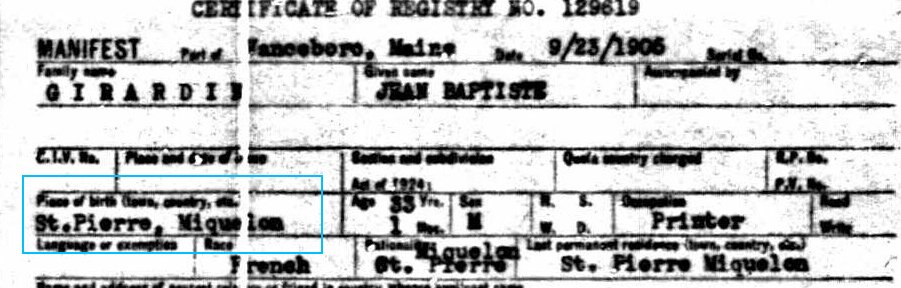

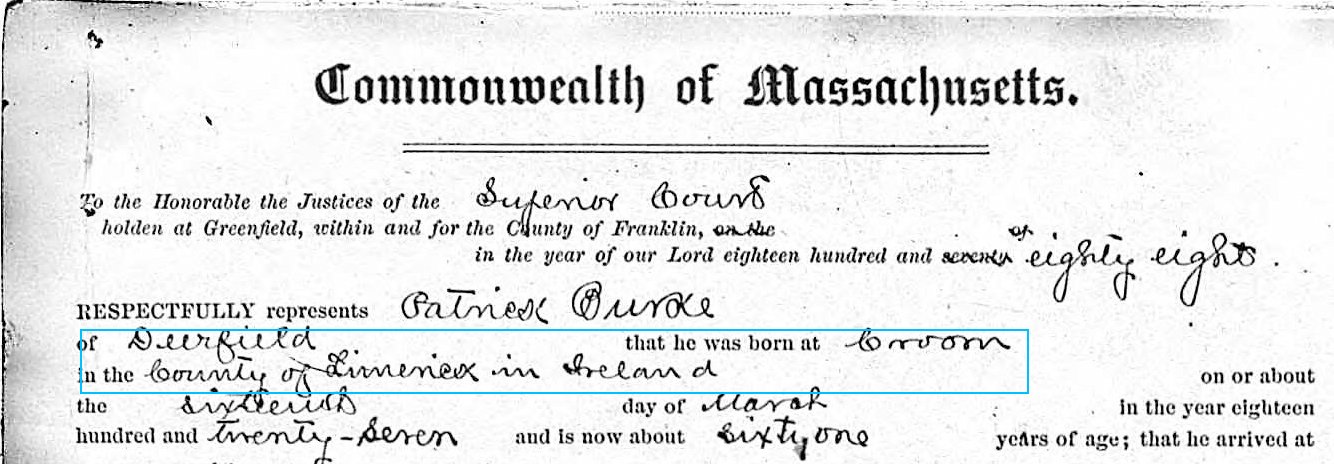

5. Naturalization records

Naturalization records can be great for pinpointing birthplaces. Many are now digitized and online, too.

While many of the earlier naturalization files give only a country of birth, they can reveal the towns or counties where the person was born.

My 3x great grandfather’s naturalization showed he came from Croom, County Limerick, Ireland. This is the only document I’ve found that gave a townland, let alone a county for his birth.

Later records have a treasure trove of genealogical information, including where children were born and other names the immigrant used.

6. Alien registration files

If your immigrant ancestor was in the US in 1940, they might have an alien registration file. “A-Files” can be a genealogy gold mine. They can tell you when and where someone was born, when and where they arrived, and maiden names. If they traveled back to their home country, their file would note travel dates and the address they would be staying at.

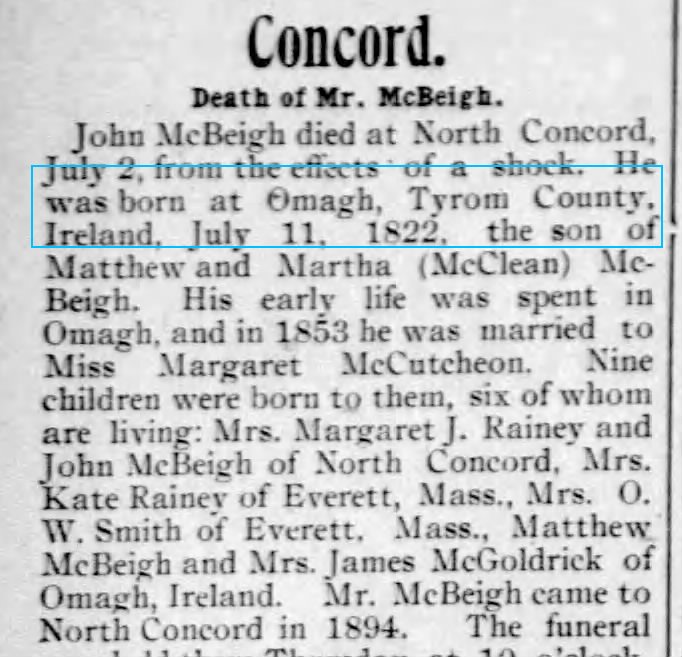

7. Obituaries

Obituaries are fabulous resources for unearthing not only hometowns but other biographical points.

Image via Newspapers.com. St. Johnsbury Caledonian, 10 July 1907.

8. Military records

Many immigrants served in the military and may also be war veterans. Military records like draft registrations and service files often state places of birth.

Pension files may also have copies of church or vital records or family bibles with notes about where the person was from.

9. Passport applications

If your ancestor ever went back to visit family, you may be able to locate a passport application.

While passports weren’t required until 1941, many immigrants applied for one to prove their citizenship when traveling abroad. In fact, people filed over 168 million applications before 1941 so there is a chance your ancestor may be one.

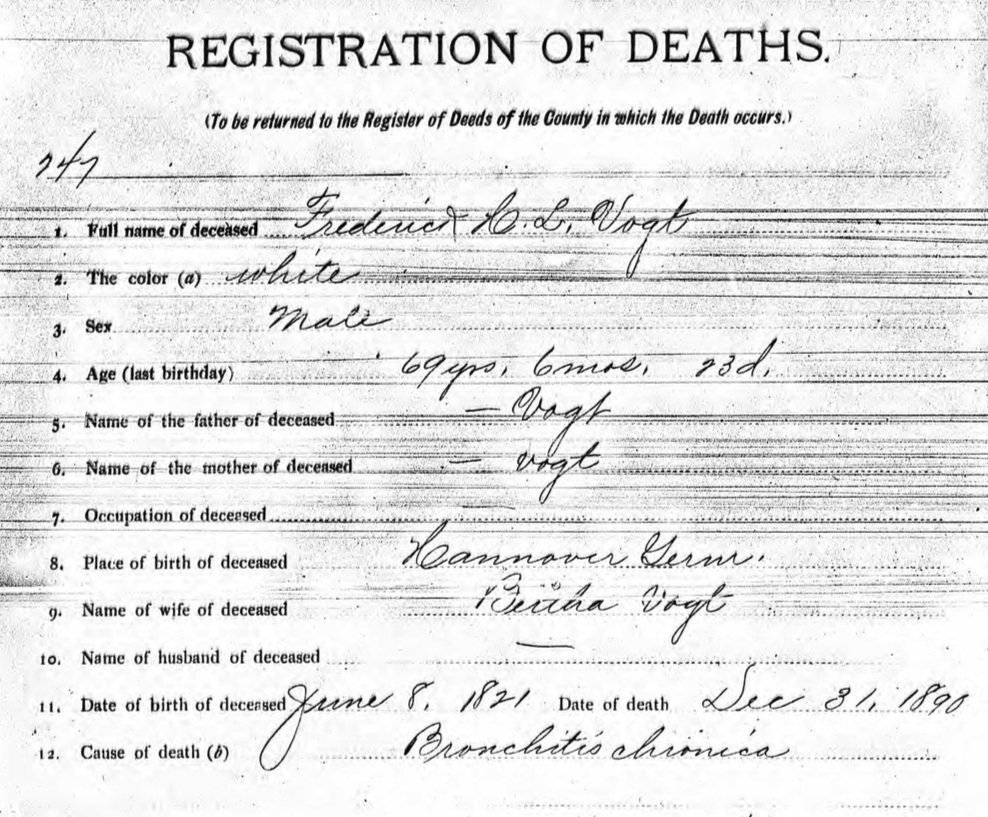

10. Vital records

And of course, we can’t forget vital records as a potential place to discover where your ancestor was born. While they often have only the country of birth, you can learn a county or region so you can narrow down your research to a geographic area. Sometimes they name an exact place.

Look for all the birth, marriage, and death records for your ancestor and their kids. If their siblings also immigrated, look for the vital records for them and their children, too.

Related posts:

What you need to know about Mexican civil registration records

9 French Canadian Genealogy Books to Energize Your Research

14 Useful Free Resources for Hispanic Genealogy

Other useful sources to look for your ancestor’s hometown

If you still haven’t had any luck, other potential sources of hometown information are:

Social security applications

County and local history books

Criminal records

Ethnic/foreign language newspapers

Fraternal organization records

Local genealogical and historical society records

Court records for name changes

Newspaper local news and gossip columns

Tombstone inscriptions

Final thoughts

Discovering where your family was from is like the holy grail in genealogy. These 10 types of US records are a great place to start searching for the birthplace of your ancestors. You may need to search for several types of documents to unearth and confirm someone’s hometown.

To help you get a sense of what US records can help, try using a US census immigration worksheet to gather all the clues about when they arrived and where they came from.

What other records have you used to learn where your family came from?

Was this article helpful? Please show your support and buy me a coffee through the button below. Thank you for supporting my small business!